|

During sale of DVD-Boxset

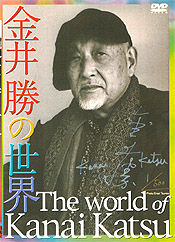

[The World of Kanai Katsu]

(with

English Subtitles, 6works, 5disks)

-:)))))))))))))))

The price for the personal use of DVD-Box is \20,000.

The price for university use etc. is \50,000.

Kanai katumaru production

k-katsu72(at-mark)mail.hinocatv.ne.jp *(at-mark = @)

katsu72maru(at-mark)yahoo.co.jp

As for the orders from the foreign countries, it is convenient :-))))))))))

Japan publications Trading Co.LTD is in charge of the business withthe foreign countries.

Please do e-mail to Mr.Watanabe for details. E-mail: r-watanabe(at-mark)jptco.co.jp

.

|